Coronavirus: The Canary in the Coal Mine of the World Economy?

13th March 2020

Tom Buncle, Yellow Railroad, has written a very informative and interesting blog on Coronavirus and the TMI is featuring it here as a guest blog this month.

It feels strange to be writing about the impact of Coronavirus on the world economy when its full anticipated impact on the health of the country from which I write, the UK, has yet to be felt. But it has already had a significant impact on business around the world, and not least the travel business. How it will pan out remains to be seen. But it is worth considering the impact it might have beyond health concerns and whether our world will return to ‘normal’, or whether some changes might be long-lasting and structural.

Is Coronavirus (COVID-19) the canary that warns us we cannot continue as we are? That our expectations of instant gratification, 'just-in-time' production systems, and unbridled carbon consumption are symptoms of a world that is creaking at the seams? Or will it merely nudge us in a slightly different direction, once we have come to terms with the impact of this crisis?

Tragic as any death related to this disease is, the impact on health is competently discussed by medical commentators elsewhere. My focus here is on the long-term economic impact on travel. We must assume that, like most epidemics, this one will pass and most people will return to normal health. But can we assume the same will be true of the global economy and the tourism sector? I think not. It is possible the changes that will be required in our behaviour during this epidemic, as well as the psychological impact of this global disease, may embed themselves as a ‘new normal’ form of behaviour – a change from which we do not return to things as they were, but we find new ways of satisfying perennial desires and modify our travel behaviour in light of what we have just experienced. This is less a pessimistic perspective than a recognition of the need to rise to the challenge of a different future.

Global Impact

Economic indicators are dismally clear. Already there is talk in the media of an economic impact equivalent to the 2008 financial crisis. Global shipping, which is heavily dependent on China, is significantly down, with more container ship tonnage now idle around the world than during the 2008 financial crisis. The FTSE 100 Index has dropped more dramatically (-8%) than after 9/11 (-6%). Oilhas dropped by around 30% to almost $30 p. barrel. Infected regions have been cordoned off - from Wuhan to Northern Italy. Many people have stopped travelling, partly for fear of catching or spreading the disease, or just of being quarantined in a hotel far from home.  Planes are looking for passengers and many flights have been cancelled worldwide as passengers stop booking or airlines decide not to fly to significantly infected areas. Sporting events, conferences and festivals are being cancelled around the world. Even the release of the new Bond film, 'A Time to Die', has been postponed until November - whether out of concern for public sensitivity or poor box office takings is a moot point. IATApredicts airlines around the world could lose up to $113 billion in passenger revenue as a result of Coronavirus. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) is forecasting a surprisingly modest decline of 1-3% in global tourist arrivals, albeit compared to previous forecasts of 3-4% growth for this year, amounting to an estimated loss of US$ 30 to 50 billion in international tourism receipts.

Planes are looking for passengers and many flights have been cancelled worldwide as passengers stop booking or airlines decide not to fly to significantly infected areas. Sporting events, conferences and festivals are being cancelled around the world. Even the release of the new Bond film, 'A Time to Die', has been postponed until November - whether out of concern for public sensitivity or poor box office takings is a moot point. IATApredicts airlines around the world could lose up to $113 billion in passenger revenue as a result of Coronavirus. The United Nations World Tourism Organization (UNWTO) is forecasting a surprisingly modest decline of 1-3% in global tourist arrivals, albeit compared to previous forecasts of 3-4% growth for this year, amounting to an estimated loss of US$ 30 to 50 billion in international tourism receipts.

This has a consequent impact on tourism businesses and many others in the visitor economy supply chain worldwide. If planes aren’t flying and people aren’t travelling, hotels restaurants, visitor attractions and tourism sites will have no customers; and no customers means profit warnings at best and, sadly more likely, redundancies and businesses going under. For many tourism businesses, particularly those dependent on international tour operators to provide them with clients as opposed to those more reliant on independent, direct bookings, the loss of a few weeks’ business now and subsequent cancellations, can mean little prospect of recovery before next year. Similarly, outbound tour operators and inbound destination management companies will also take a hit as bookings stall. The longer this situation lasts, the less able such businesses will be to survive the immediate impact of this visitor dearth.

Implications for Tourism

So, what might be the long-term effect of this potentially considerable shakeout of tourism businesses around the world?  How might it affect the way people travel?

How might it affect the way people travel?

Will the pendulum swing back to where it was before we heard of Coronavirus? Or will it find a new equilibrium? Here are a few thoughts and questions about how things might change in the global tourism sector after the world returns to normal health.

- Business cull: Many of these businesses will not come back to life or be replaced. They are likely to be gone forever, reducing the capacity to accommodate what has up till now been an unquenchable flow of tourists. Certainly new businesses will eventually emerge in many places; and visitor demand is also likely to return, albeit more quickly to some places than others. But the financial capacity to replace all such businesses, many of which will be small, and often lifestyle, businesses, is unlikely to be universal.

- Impact on remote communities: Some will say this ‘cull’ is a good thing, as it is likely to weed out poorer performing and lower quality businesses. But this is not a universal truth. Tourism businesses in more economically fragile, remote, and less visited areas are likely to suffer disproportionately, as their viability is likely to have been less robust. Consequently, the impact on remoter areas is likely to be more acutely felt and take much longer to recover than in mainstream and more popular tourism areas. Psychologically too, the volatility of the tourism economy, which Coronavirus has exposed, may discourage immediate reinvestment in more economically fragile areas.

On a positive note, those businesses that do survive, are likely to come back stronger as a result of their experience; and new businesses, which will inevitably eventually spring up, may be more resilient, having learnt from observing the experience of others. That said, the future is likely to favour larger businesses, because they will be more financially stable, than smaller, more local businesses, which contribute so much authentic character to the visitors’ experience. Sadly, smaller, and particularly rural, businesses may be the biggest casualty of this crisis.

- ‘Flygskam’: There is anecdotal evidence that ‘flight-shaming’ is beginning to have a slight impact on how some people travel, particularly amongst families whose children call their parents to account for what Greta Thunberg and others have encouraged them to view as environmentally negligent behaviour. Although growing, this is not yet statistically significant. But the Coronavirus-inspired lull in air travel may accelerate this trend to reduce flying after things return to ‘normal’. Certainly, as people put their international travel plans on hold, their desire for a break is unlikely to dissipate. But where they take that break and how they travel may change.

- Staycation: In many cases this may merely result in postponement of holidays. But, depending how long the fear of contagion endures, pent-up demand is likely to encourage more people to take a break in their own country. The more they see of their own country as tourists, which many may have not considered doing before, the more they may be surprised by the quality of accommodation, food and range of activities. This may spark a slight redress in the balance between foreign and domestic breaks. Discovering their own country can offer what they travel overseas for may increase their propensity to consider including a ‘staycation’ in future holiday plans, perhaps in place of at least one break they might otherwise have taken abroad.

- Business travel and cost-cutting: I suspect this may be one of the areas in which a ‘new normal’ is most starkly established after the disease has run its course. With face-to-face meetings and conferences cancelled or postponed around the world, and people encouraged to self-isolate and work from home to minimise the spread of infection, many will realise they can still conduct their business pretty efficiently without travelling. Add to that the cost saving, plus the corporate kudos of reducing carbon emissions, and you have a ‘triple-win’ situation. Of course business travel will return, and conferences will still be held. But they may be reduced, as businesses re-assess their necessity and opt to reduce costs, environmental impact, and time lost travelling. Ciscorecently cut $100 million a year off of their corporate travel by insisting staff use telecommunications and only travel where essential. Conducting business by ‘telepresence’ is increasingly becoming the norm, particularly in the USA and for internal organisational business. Interestingly, an innovative online meeting place was established for disappointed delegates, following the recent cancellation of ITB Berlin, the world’s largest travel trade fair. Might such ‘virtual conventions’, like webinars, increasingly replace some conferences and trade shows?

- Aviation routes: The longer the impact of the virus lasts, the more we are likely to see less commercially viable airlines go bust. Flybe is the highest profile airline to have collapsed. But, to attribute its demise to Coronavirus is a red herring. Flybe’s business model was inherently unsustainable. There may have been enough traffic to sustain flights between secondary airports within the UK. But extending this to less viable routes in continental Europe, on which there was insufficient year-round demand, and then burdening itself with the cost of the planes required to service these routes, was a recipe for disaster. One thing Flybe’s demise does tell us, though, is that fragile routes to and between secondary cities are unlikely to be viable without some sort of subsidy or government-imposed Public Service Obligation. Loganair has already stepped in to service higher traffic routes such as Edinburgh-Manchester, Aberdeen-Belfast et al. But it is hard to see who might pick up some of the economically flimsier routes.

- Visitor Behaviour: Postponing foreign holidays and more staycations may be one outcome of this crisis. But people might also be encouraged to consider more foreign holidays closer to home, to eschew the exotic in favour of the familiar and, probably more significantly, to ‘stop and smell the roses’ on their travels: slower travel, focusing on enjoying the place, rather than rushing from one to another in a destination collection frenzy. Apart from the fact that there is already a trend towards such slower, experiential travel, I have no evidence that this crisis might provoke a step change in the pace of this trend. All I’m suggesting is that such a reaction might be consistent with the psyche underlying the growing ‘slow tourism’ movement and a possible lingering disquiet about less well known, more distant destinations, the fragility of whose medical infrastructure may have been exposed by the Coronavirus outbreak, at least for a year or two after this crisis.

- Group travel: Two things have brought home the infection risk more forcefully than ever before: the worldwide cancellation of sporting events, conferences and many other public gatherings; and relentless governmental advice about public hygiene, including keeping a one metre 'social distance', as advised by the World Health Organization (WHO). Obviously this will affect travel in the short-term, where people would be in unavoidably close proximity to each other, such as bus tours and on planes. But, will this enhanced awareness of social distance outlast the virus and become a permanent consideration influencing the type of holiday people choose? Might we see a growing reluctance to travel in groups, a hesitancy about being thrown together with people whose social and medical history is unknown and which might now be a source of apprehension in a way it never was before, thereby accelerating the trend towards independent travel and dynamic packaging? Hopefully not. The joy of mixing and meeting with people from other cultures and countries will hopefully forever trump any misplaced fear of the unknown and different, which is one of the appeals of group travel.

- Cruise: How will cruises be affected? High profile news coverage of outbreaks on cruise ships held in Yokohama and off the Californian coast, plus fear of being quarantined in such a confined environment will not encourage bookings in the short-term. Nor will the rather startling warning-cum-edict by the US State Department to avoid taking cruises. Will this memory, and a shared hesitancy with group travellers about unavoidable proximity, have a longer-term effect on cruise travel, especially as the passenger demographic tends towards more vulnerable cohorts?

- Family bonding: After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, there was a marked increase in families travelling together, particularly three generations (grandparents, parents and children), not least in the USA. This was a reaction to the incomprehensible trauma and a desire to stay close to loved ones. Might we see a similar recommitment to family values, expressed in more holidays taken together as families, even if only for a year or two?

- Social media and trust: A notorious source of fake news and scaremongering, at times of crisis social media can stoke fear as much as reassure. Might we see a backlash against 'anti-social' media and more clustering around social media sites, apps, commentators and influencers perceived as credible and authoritative, as people seek sources they can trust? A sort of self-imposed order on the anarchic, over-sharing world of social media? Perhaps too, we might see the big channels take more responsibility for the content they enable. Facebook recently promised to remove content that included conspiracy theories, which have been debunked by the World Health Organization and other credible health experts. Twitter has launched a #KnowTheFacts initiative, in direct response to Coronavirus misinformation. Could we see a two-track social media network develop, whereby sources and channels percieved as authoritative and truthful predominate? What impact might that have for peer-to-peer credibility? It certainly might attract a premium from advertisers – “advertise with the oracle of truth for a fair price, or get lost amongst peddlers of misinformation for peanuts”?

- Pull up the drawbridge or greater international cooperation? As the virus struck, we saw some countries close their doors to certain nationalities or people from disproportionately infected areas. Apart from its discriminatory nature, this is not economically viable in the long-term. But, the other side of this coin is the global impact of this virus, which has brutally demonstrated what a globally interconnected world we live in. When one country catches a cold, we all do. We depend on each other, not just for trade, but for information about the level of contamination in other countries, so we can make decisions about how to address it in our own. Might this experience encourage greater international cooperation and openness, out of self-interest? Might it be the turning point for the pendulum of protectionism?

- Shorter time horizons: Holidaymakers have tended to book later and later in many countries over the last few years. In some countries this may be partly attributed to cultural traits; but the internet has also enabled this worldwide. Add to this digital opportunity an imperative to wait and see when a crisis hits, and you can envisage how this could become a more ingrained behaviour. This mindset could last long after the crisis is over, not least because you never know when another might erupt and you’d be wise to hedge your bets until you absolutely have to commit to booking. The implication of this for tourism businesses is the need to be nimble and able to respond quickly, not just to crises as they emerge, but also to last minute travellers’ requests. The days of holding clients’ money for several weeks before handing it over may have been dwindling for some time; but this source of boosting cash flow is only likely to decline further, as booking lead times continue to shrink.

Conclusion

Catalyst for Change

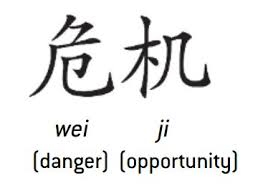

The oft-quoted silver lining associated with a crisis is the opportunity it presents to clean the Augean stables of complacency. The Chinese word for crisis includes two characters: one meaning ‘danger’ and the other ‘opportunity’* – the idea being we learn from it and improve our systems and business practices to face the future. Sometimes we do; sometimes we don’t. The greater the crisis, the more likely we will. This is not just a considerable crisis; it is also global.

Our chances of learning from it and changing the way we do things are therefore favourable – not least when changing consumer tastes and behaviour may leave us with no option.

By stopping some business dead in its tracks, Coronavirus will unquestionably be a catalyst for change. In making us take stock of our business propositions, consider future markets, and explore potential new opportunities in order to survive, embryonic underlying trends may reveal themselves, which might otherwise pass unnoticed in the hurly-burly of normal business. It may be overstating their impact to suggest any of these changes might amount to a statistically discernible shift in travel behaviour in the immediate future. Nevertheless, they may presage subtle changes in direction, which could grow into significant trends over the next few years. This may be an opportunity for some destinations and businesses to get ahead of the game.

Some detriment

In summary, the main downsides are likely to be: a cull of tourism businesses, with a disproportionate impact on remoter and rural areas; a conservative approach to reinvestement in tourism businesses, and therefore slower pace of recovery beyond major tourism 'honeypots'; job losses in the tourism sector and its extensive supply chain; less air connectivity between secondary destinations; fewer air services to less popular countries; and reduced tourism receipts in many destinations around the world for a year or more.

But discretionary leisure travel has become so much an essential part of people’s lives in developed economies that it can be expected to revive quite quickly. Tourism generally returned to pre-crisis levels in about a year after the 2003 SARScrisis. The impact of Coronavirus is likely to be considerably greater than SARS, which might mean a slightly longer recovery period for some destinations. But recover it will.

But positives too

Some more positive impacts might come from a change in travelling behaviour amongst a certain percentage of travellers, including: a growth in domestic travel – ‘staycations’; more time spent in one place – ‘slower’ travel; greater respect for places as a result of ‘slower’ travel, whereby people behave more as ‘travellers’ than ‘tourists’; more family travel; reduced environmental impact, as people reduce their travel frequency and stay longer in one place, with a potential reduction in travel to overcrowded tourism hotspots.

Places that appeal to ‘slower’ travellers and develop their destinations accordingly, may well find an increased appetite for what they offer. Remoter destinations that work to improve their connectivity and trumpet their distinctive appeals will be better placed to overcome their disproportionate disadvantages. And those businesses that are agile in responding to changing visitor tastes and shorter booking lead times will bounce back more quickly. History tells us tourism is an incredibly resilient sector. We are likely to see a return to global growth in 2021-2022.

Other lessons

Meanwhile, would it be too much to hope that we might also have learnt some abiding lessons from this crisis? Could it help us to put future crises in perspective? Might it teach us the futility of intemperate and irrational responses, which don’t help in either minimising the spread or understanding the risk of an epidemic, – to wit the widespread panic-buying of toilet paper and a universal obsession with face masks which, to quote the CEO of the European Tour Operators’ Association, are as clinically effective a prophylactic ‘as rubbing yourself with a dead pigeon to cure the plague or striking an offending body part with a bible to cure syphilis’, both of which were, in their day, popularly espoused? We can but hope – both for a return to a healthy visitor economy worldwide and a swift end to this insidious disease.

[*This is a slightly distorted interpretation of the true linguistic meaning of the second of these two juxtaposed characters, 'ji'. But their combination has been widely interpreted as conceptually close to this meaning and 'constructively misinterpreted' for many years, both in the west and by some native Chinese speakers.]

0 comments

Leave a comment